T H E P L A I N D E A L E R.

NO. 1.

SATURDAY, DECEMBER 3, 1836.

VOL. I.

THE POLITICAL PLAINDEALER.

The immediate cause of all the mischief of misrule is that the men acting as the representatives of the people have a private and sinister interest, producing a constant sacrifice of the interests of the people.

JEREMY BENTHAM.

PREFATORY REMARKS.

THE first number of the PLAINDEALER was to be issued so soon after the announcement of an intention to publish such a journal, that it was not thought necessary to precede it with a very elaborate prospectus; the more particularly as the editor’s connexion with the EVENING POST for eight years previous, during a considerable portion of which time that paper was under his sole direction, had made the publick very generally acquainted with his views on all the leading questions of politicks and political economy, and with his mode of treating those subjects. Instead of the swelling promises which usually herald a publication of this kind, it was therefore deemed better to let the work speak for itself, and to depend for its success, from the first, as we eventually must, on the intrinsick qualities by which it should be distinguished. The same reasons which obviated the necessity of a particular prospectus, suggest the propriety of indulging in but a brief preliminary address. The PLAINDEALER is now before the reader, and must speak for itself. There are always circumstances to be encountered at the outset of an undertaking like this which diminish the merits of a first number, and which therefore authorize us to express, with some confidence, a hope that future numbers may be better. We think we can at least safely promise that equal claims shall be maintained.

The title chosen for this publication expresses the character which it is intended it shall maintain. In politicks, in literature, and in relation to all subjects which may come under its notice, it is meant that it shall be a PLAINDEALER. But plainness, as it is hoped this journal will illustrate, is not incompatible with strict decorum, and a nice regard for the inviolability of private character. It is not possible, in all cases, to treat questions of publick interest in so abstract a manner as to avoid giving offence to individuals; since few men possess the happy art which Sheridan ascribes to his Governour in the Critick, and are able entirely to separate their personal feelings from what relates to their publick or official conduct and characters. It is doubtful, too, if it were even practicable so to conduct the investigations, and so to temper the animadversions of the press, as, in every instance, “to find the fault and let the actor go,” whether the interests of truth would, by such a course, be best promoted. The journalist who should manage his disquisitions, would indeed exercise but the “cypher of a function.” His censures would be likely to awaken but little attention in the reader, and effect but little reformation in their object. People do not peruse the columns of a newspaper for theoretick essays, and elaborate examinations of abstract questions; but for strictures and discussions, occasional in their nature, and applicable to existing persons and events. There is no reason, however, why the vulgar appetite for abuse and scandal should be gratified, or why, in maintaining the cause of truth, the rules of good breeding should be violated. Plaindealing requires no such sacrifice. Truth, though it is usual to array it in a garb of repulsive bluntness, has no natural aversion to amenity; and the mind distinguished for openness and sincerity may at the same time be characterized by the high degree of urbanity and gentleness. It will be one of the aims of the Plaindealer to prove, by its example, that there is at least nothing utterly contrarious and irreconcilable in these traits.

In politicks, the Plaindealer will be thoroughly democratick. It will be democratick not merely to the extent of the political maxim, that the majority have the right to govern; but to the extent of the moral maxim, that it is the duty of the majority so to as to preserve inviolate the equal rights of all. In this large sense, democracy includes all the principles of political economy: that noble science which is silently and surely revolutionizing the world; which is changing the policy of nations from one of strife to one of friendly emulation: and cultivating the arts of peace on the soil hitherto desolated by the ravages of war. Democracy and political economy both assert the true dignity of man. They are both the natural champions of freedom, and the enemies of all restraints on the many for the benefits of the few. They both consider the people the only proper source of government, and their equal protection its only proper end; and both would confine the interference of legislation to the fewest possible objects, compatible with the preservation of social order. They are twin-sisters, pursuing parallel paths, for the accomplishment of cognate objects. They are sometimes found divided, but always in a languishing condition; and they can only truly flourish where they exist in companionship, and, hand in hand, achieve their kindred purposes.

The Plaindealer claims to belong to the great democratick party of this country; but it will never deserve to be considered a party paper in the degrading sense in which that phrase is commonly understood. The prevailing errour of political journals is to act as if they deemed it more important to preserve the organization of party, than to promote the principles on which it is founded. They substitute the means for the end, and pay that fealty to men which is due only to truth. This fatal errour it will be a constant aim of the Plaindealer to avoid. It will espouse the cause of the democratick party only to the extent that the democratick party merits its appellation and is faithful to the tenets of its political creed. It will contend on its side while it acts in conformity with its fundamental doctrines, and will be found warring against it whenever it violates those doctrines in any essential respect. Of the importance and even dignity of party combinations, no journal can entertain a higher and more respected sense. They furnish only certain means of carrying political principles into effect. When men agree in their theory of government, they must also agree to act in concert, or no practical advantage can result from their accordance. “For my part,” says Burke, “I find it impossible to conceive that any one believes in his own politicks, or thinks them to be of any weight, who refuses to adopt the means of having them reduced to practice.”

From what has been already remarked, it is matter of obvious inference that the Plaindealer will steadily and earnestly oppose all partial and special legislation, and all grants of exclusive or peculiar privileges. It will, in a particular manner, oppose, with its utmost energy, the extension of the pernicious bank system with which this country is cursed; and will zealously contend, in season and out of season, for the repeal of those tyrannous prohibatory laws, which give to the chartered money-changers their chief power of evil. To the very principle of special incorporation we here, on the threshhold of our undertaking, declare interminable hostility. It is a principle utterly at war with the principles of democracy. It is the opposite of that which asserts the equal rights of man, and limits the offices of government to his equal protection. It is, in its nature, an aristocratick principle; and if permitted to exist among us much longer, and to be acted upon by our legislators, will leave us nothing of equal liberty but the name. Thanks to the illustrious man who was called in a happy hour to preside over our country! the attention of the people has been thorougly awakened to the insidious nature and fatal influences of chartered privileges. The popular voice, already, in various quarters, denounces them. In vain do those who possess, and those who seek to obtain grants of monopolies, endeavour to stifle the rising murmur. It swells louder and louder; it grows more and more distinct; and is spreading far and wide. The days of the charter-mongers are numbered. The era of equal privileges is at hand.

There is one other subject on which it is proper to touch in these opening remarks, and on which we desire that there should exist the most perfect understanding with our readers. We claim the right, and shall exercise it too, on all proper occasions, of absolute freedom of discussion. We hold that there is no subject whatever interdicted from investigation and comment; and that we are under no obligation, political or otherwise, to refrain from a full and candid expression of opinions as to the manifold evils, and deep disgrace, inflicted on our country by the institution of slavery. Nay more, it will be one of the occasional but earnest objects of this paper to show, by statistical calculations and temperate arguments, enforced by every variety of illustration that can properly be employed, the impolicy of slavery, as well as its anormous [2] wickedness: to show its pernicious influence on all the dearest interests of the south; on its moral character, its social relations, and its agricultural, commercial and political prosperity. No man can deny the momentous importance of this subject, nor that it is one of deep interest to every American citizen. It is the duty, then, of a publick journalist to discuss it; and from the obligations of duty we trust the Plaindealer will never shrink. We establish this paper, expecting to derive from it a livelihood; and if an honest and industrious exercise of such talents as we have can achieve that object, we shall not fail. But we cannot, for the sake of livelihood, trim our sails to suit the varying breeze of popular prejudice. We should prefer, with old Andrew Marvell, to scrape a blade-bone of cold mutton, to faring more sumptuously on vainds obtained by the surrender of principle.* If a paper, which makes the right, not the expedient, its cardinal object, will not yield its conductor a support, there are honest vocations that will; and better the humblest of them, than to be seated at the head of an influential press, if its influence is not exerted to promote the cause of truth.

* The story to which allusion is here made cannot too often be repeated. We copy it from a life of Marvell, by John Dove. It is as follows: The borough of Hull, in the reign of Charles II, chose ANDREW MARVELS, a young gentleman of little or no fortune, and maintained him in London for the service of the publick. His understanding, integrity, and spirit, were dreadful to the then infamous administration. Persuaded that he would be theirs for properly asking, they sent his school-fellow, the LORD TREASURER DANBY, to renew acquaintance with him in his garret. At parting, the Lord Treasurer, out of pure affection, slipped into his hand an order upon the Treasury for 1,000l., and then went to his chariot. Marvell looking at the paper calls after the Treasurer, “My Lord, I request another moment.” They went up again to the garret, and Jack, the servant boy, was called. Jack, child, what had I for dinner yesterday?” “Don’t you remember, sir? you had the little shoulder of mutton that you ordered me to bring you from a woman in the market.” “Very right, child. What have I for dinner to-day?” “Don’t you know, sir, that you bid me lay by the blade-bond to broil?” “’Tis so, very right, child, go away. My Lord, do you hear that? Andrew Marvell’s dinner is provided; there’s your piece of paper. I want it not. I knew the sort of kindness you intended. I live here to serve my Constituents; the Ministry may seek men for their purpose; I am not one.”

THANKSGIVING DAY.

Thursday, the fifteenth of the present month, has been designated by Governour Marcy, in his annual proclamation, as a day of general thanksgiving throughout this state. This is done in conformity with a long established usage, which has been so generally and scrupulously observed, that we doubt whether it has ever been pretermitted, for a single year, by the Chief Magistrate of any state in the Confederacy. The people, too, on these occasions, have always responded with such cordiality and unanimity to the recommendation of the Governours, that not even the Sabbath, a day which the scriptures command to be kept holy, is more religiously observed, in most places, than the day set apart as one of thanksgiving and prayer by gubernatorial appointment. There is something exceedingly impressive in the spectacle which a whole people presents, in thus voluntarily withdrawing themselves on some particular day, from all secular employment, and uniting in a tribute of praise for the blessings they enjoy. Against a custom so venerable for its age, and so reverently observed, it may seem presumptuous to suggest an objection; yet there is one which we confess seems to us of weight, and we trust we shall not be thought governed by an irreligious spirit, if we take the liberty to urge it.

In framing our political institutions, the great men to whom that important trust was confided, taught, by the example of other countries, the evils which result from mingling civil and ecclesiastical affairs, were particularly careful to keep them entirely distinct. Thus the Constitution of the United States mentions the subject of religion at all, only to declare that “no religious test shall ever be required as a qualification to any office or publick trust under the United States.” The Constitution of our own state specifies that “the free exercise and enjoyment of religious profession and worship, without discrimination or preference, shall forever be allowed in this state, to all mankind;” and so fearful were the framers of that instrument of the dangers to be apprehended from a union of political and religious concerns, that they inserted a clause of positive interdiction against ministers of the gospel, declaring them forever ineligible to any civil or military office or place within the state. In this last step we think the jealousy of religious interference proceeded too far. We see no good reason why preachers of the gospel should be partially disenfranchised, any more than preachers against it, or any more than men devoted to any other profession or pursuit. This curious proscriptive article of our Constitution presents the startling anomaly, that while an infidel, who delivers stated Sunday lectures in a tavern, against all religion, may be elected to the highest executive or legislative trust, the most liberal and enlightened divine is excluded. In our view of the subject neither of them should be proscribed. They should both be left to stand on the broad basis of equal political rights, and the intelligence and virtue of the people should be trusted to make a selection from an unbounded field. This is the true democratick theory; but this is a subject apart from that which is our present purpose to consider.

No one can pay the most cursory attention to the state of religion in the United States, without being satisfied that its true interests have been greatly promoted by divorcing it from all connexion with political affairs. In no other country of the world are the institutions of religion so generally respected, and in no other is so large a proportion of the population included among the communicants of the different christian churches. The number of christian churches of congregations in the United States is estimated, in a carefully prepared article of the religious statisticks in the American Almanack of the present year, at upwards of sixteen thousand, and the number of communicants at nearly two millions, or one tenth of the entire population. In this city alone the number of churches is one hundred and fifty, and their agregate capacity is nearly equal to the accommodation of the whole number of inhabitants. It is impossible to conjecture, from any data within our reach, the amount of the sum annually paid by the American people, of their own free will, for the support of the ministry, and the various expenses of their religious institutions; but it will readily be admitted that it must be enormous. These, then, are the auspicious results of perfect free-trade in religion—of leaving it to manage its own concerns, in its own way, without government protection, regulation, or interference, of any kind or degree whatever.

The only instance of intermeddling, on the part of the civil authorities, with the matters which, being of a religious character, properly belong to the religious guides of the people, is the proclamation which it is the custom for the Governour of each state annually to issue, appointing a day of general thanksgiving, or a day of general fasting and prayer. We regret that even this single exception should exist to that rule of entire separation of the affairs of state from those of the church, the observance of which in all other respects has been followed by the happiest results. It is to the source of the proclamation, not to its purpose, that we chiefly object. The recommending a day of thanksgiving is not properly any part of the duty of a political Chief Magistrate: it belongs, in its nature, to the heads of the church, not to the head of the state.

It may very well happen, and, indeed, it has happened, in more instances than one, that the chief executive officer of a state has been a person, who, if not absolutely an infidel or sceptick in religious matters, has at least, in his private sentiments and conduct, been notoriously disregardful of religion. What mockery for such a person to call upon the people to set apart a day for returning their acknowledgments to Almighty God for the bounties and blessings bestowed upon them! But even when the contrary is the case, and it is well known that the Governour is a strictly religious man, he departs very widely from the duties of his office, in proclaiming, in his gubernatorial capacity, and under the seal of the state, that he has appointed a particular day as a day of general thanksgiving. This is no part of his official business, as prescribed in the Constitution. It is not one of the purposes for which he was elected. If it were a new question, and a Governour should take upon himself to issue such a proclamation for the first time, the proceeding could scarcely fail to arouse the most sturdy opposition from the people. Religious and irreligious would unite in condemning it: the latter as a gross departure from the specified duties for the discharge of which alone the Governor was chosen; and the former as an unwarrantable interference of the civil authority with ecclesiastical affairs, and a usurpation of the functions of their own duly appointed ministers and church officials. We recollect very distinctly what an excitement arose in this community a few years ago, when our Common Council, following the examples of the Governour, undertook to interfere in a matter which belonged wholly to the clerical functionaries, and passed a resolution recommending to the various ministers of the gospel the subject of their next Sunday discourse. The Governour’s proclamation would itself provoke equal opposition, if men’s eyes had not been sealed by custom to its inherent impropriety.

[3] If such a proceeding would be wrong, instituted now for the first time, can it be right, because it has existed for a long period? Does age change the nature of principles, and give sanctity to errour? Are truth and falsehood of such mutable and shifting qualities, that though, in their original characters, as opposite as the poles, the lapse of a little time may reduce them to a perfect similitude, and render them entirely convertible? If age has in it such power as to render venerable what is not so in its intrinsick nature, then is paganism more venerable than christianity, since it has existed from a much more remote antiquity. But what is wrong in principle must continue to be wrong to the end of time, however sanctioned by custom. It is in this light we must consider the gubernatorial recommendation of a day of thanksgiving; and because it is wrong in principle, and not because of any particular harm which the custom has yet been the means of introducing, we should be pleased to see it abrogated. We think it can hardly be doubted that, if the duty of setting apart a day for a general expression of thankfulness for the blessings enjoyed by the community were submitted wholly to the proper representatives of the different religious sects, they would find no difficulty in uniting on the subject, and acting in concert in such a manner as should give greatly solemnity and weight to their proceeding, than can ever attach to the proclamation of a political governour, stepping out of the sphere of his constitutional duties, and taking upon himself to direct the religious exercises of the people. We cannot too jealously confine our political functionaries within the limits of their prescribed duties. We cannot be too careful to keep entirely separate the things which belong to government from those which belong to religion. The political and the religious interests of the people will both flourish the more prosperously for being wholly distinct. The condition of religious affairs in this country proves the truth of the position; and we are satisfied it would receive still further corroberation, if the practice to which we object were reformed.

TRUE FRIENDS OF THE CONSTITUTION.

The following account of a most audacious and indecent outrage, we find copied into the Washington Globe from the New Hampshire Argus:

“An attempt was made to hold an anti-slavery meeting at the Baptist Church, in this village on Wednesday evening last. There was some excitement on that day, but not enough to lead us to suppose any decided measures would be taken to suppress the meeting. However, in the evening some half dozen abolitionists, together with some individuals whose curiousity led them in, made up the audience, and the services commenced. They went on undisturbed, until the singing of the second hymn, when the sonorous tones of a fish-horn rose without the building, accompanying the airs very like a trumpet’s blast in Martin Luther’s judgment hymn. The orator commenced his discourse, and soon the church bells sent forth a most dolourous tolling, and stones and other missiles came pouring in at the windows; and among other articles thus uncerimoniously showered in, was a bottle, whose crash upon the floor declared at once the nature of its contents. It was very evident that one or more little spotted unmentionable animals had been deprived of their only means of defence; and it truly had a most magical effect. The house was cleared instantly, and the audience, we believe, suffering no serious bodily injuries or inconvenience, barring perhaps a slight rebellion among the weaker stomachs.”

The above delectable paragraph is not merely copied into the Washington Globe, but is accompanied with comments showing that the outrageous conduct of the rioters meets with the approval of that print. The Globe speaks in a phrase of eulogy of the insolent and lawless mob who dared to interrupt with violence a meeting of peaceful citizens, assembled in a place of worship, for the prosecution of a lawful purpose, and terms them “the true friends of the Constitution!” Was there ever a more shameful perversion of language? Friends of the Constitution! The preamble of that instrument states, as one of the chief motives which led to its being established, that it was to “secure the blessings of liberty.” It is one of the blessings of liberty that a body of respectable citizens may not assemble to interchange their sentiments and opinions on a subject of momentous interest to every thinking being in the United States, without being liable to be interrupted by a gang of ruffians, to have their deliberations drowned with yells and clamour, and their persons maltreated? Is this one of the blessings of liberty which the Constitution was intended to secure? It must be so, if the men who committed the outrage are indeed “the true friends of the Constitution.” One of the articles of that instrument expressely enjoins that “Congress shall make no law abridging the freedom of speech or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the government for a redress of grievances.” Yet it seems that a mob of intolerant and tumultuous wretches have powers denied to Congress, and in forcibly violating the freedom of speech and dispersing people peaceably assembled to consider the propriety of petitioning the government on an important subject, they prove themselves to be “the true friends of the Constitution!” Such sentiments as these would sound strange and discordant enough uttered by almost any newspaper; but coming from the semi-official organ of the government, we confess they are well calculated to startle every reader who in sober earnestness deserves to be styled a true friend of the Constitution.

BREACH OF PRIVILEGE.

In the proceedings of the Board of Aldermen, a fortnight ago, we noticed that the butchers of some four or five of the principal markets had presented petitions, complaining that while they are compelled to pay high premiums and rents for their stalls in the markets, they are suffered to be injured by the numerous meat shops existing in the city, in defiance of the laws. Nothing can be more reasonable than this complaint, and it is, beyond all question, the bounden duty of the Common Council to take immediate measures to obviate the ground of it. While that body suffers unlicensed meat shops to exist, it permits a gross infringement of its implied contract with the regular butchers; and we do not see with what show of justice it can exact the enormous rents and premiums that the latter agreed to give as an equivalent for the exclusive privileges of monopoly, which, it seems, they do not enjoy. If the Common Council will sell monopolies, it should preserve its faith with the purchasers, and honestly give them their money’s worth. If it will interpose its own laws in the place of the laws of trade, it should see that they are duly enforced, or otherwise, between the two conflicting systems of legislation, the natural and the artificial, the community will be worse off than if in a state of absolute anarchy.

We hold, with Jeremy Bentham, that “under a government of laws, it is the motto of a good citizen, to obey punctually—to censure freely;” and this is precisely what we are prepared to do and to have done in regard to our Corporation laws concerning butchers and markets. While those laws are suffered to encumber the statute book, they ought to be rigidly enforced; and the worse the law, the more desirable that it should be put into strict execution. Two good objects are in this way affected: first, a livelier sense is created of the obligation which every good citizen is under to obey the law; and second, the publick attention is more surely called to the evil, and a remedy is more certainly and speedily demanded. In this view of the subject, therefore, we make common cause with the petitioning butchers, and call upon the Common Council to protect us in our monopoly selling meat, and to punish, to the utmost extent of its authority, the lawless conduct of those men who have audaciously set up meat shops on their own accord, and presumed to sell beef and mutton without the authority of a license, or without paying one cent into the City Treasury for the privilege. We go further than this, and call upon the Common Council to punish, in some signal manner, as participators in the crime, all those citizens against whom it can be proved that they have purchased beef or mutton from the stalls of the unauthorized meat sellers; and if it should so happen that some of its own body are implicated in this offence, the punishment could not fail to have a still more exemplary effect. [Online Editor’s Note: I strenuously disagree with much in the above paragraph, which I find to be vile. Unlicensed meat sellers should not be prosecuted or fined in any way, nor should their customers, regardless of what the Common Council may say to the contrary.]

The next step which we should recommend to the Common Council to take would be to repeal all those portions of the market laws which constrain citizens from opening meat shops when and where they please; giving, at the same time, to the butchers, who, seduced by the lure of a monopoly, have contracted to pay high rents for their stalls in the city markets, the right to relinquish those contracts or retain them, at their option. We would recommend, in short, that the Common Council should permit the laws of trade to take the place of its own clumsy and arbitrary enactments; and our word for it, would be found, in the course of a very short trial of the experiment, that the principles of political economy would regulate the whole matter much better than it has ever been regulated before. The butchers, at all events, would no longer vex the municipal authorities with remonstrances against suffering unlicensed meat sellers to violate the law. They would be effectually cured of that. A governour of one of the American colonies was informed, that a poor colonist who lived a neighbour to him, was in the habit occasionally of pilfering wood from his woodpile. “[Word unknown] be, the rascal!” exclaimed the [4] governour; “send him to me, and I will cure him, I warrant you.” When the shivering wretch appeared before him, “neighbour,” said he, “this is a dreadfully cold winter, and I am afraid your family may sometimes suffer from a want of fuel. I have enough for myself and you too; so help yourself freely at my wood-pile, for you are entirely welcome.” It is needless to add tyhat the man stole no more; and the Common Council might, by a siminal proceeding, prevent the unlicensed meat sellers from violating the law restraining them from the free exercise of that vocation. There is but one way of doing this, and that is by repealing it.

WHY IS FLOUR SO DEAR?

This question is on every body’s mouth, and the following paragraph hints the answer which the writer seems to think will explain the difficulty:

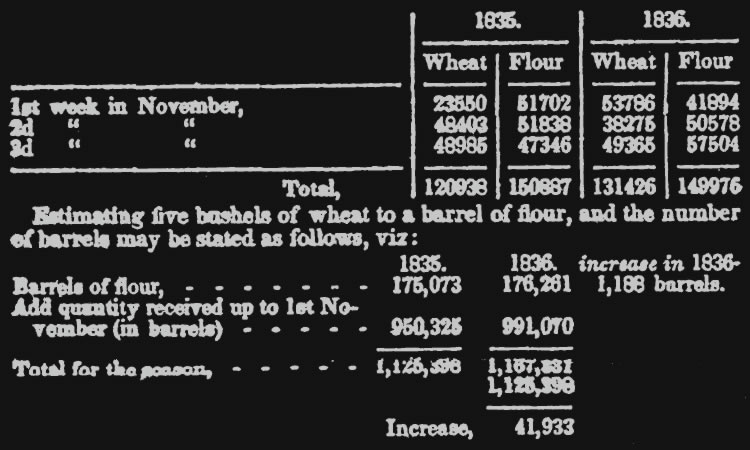

The following statement shows the quantity of wheat and flour which arrived at the tide water during the first, second and third weeks in November, in the years 1835 and 1836, viz:

The above statement of the quantity of wheat and flour brought to tide water on the canals, shows an increase for the present year over the last, of wheat equal to 41,933 barrels of flour. Without any unusual foreign demand, what has become of all the bread stuffs which have come to market through the canals? Is it a scarcity of the article of flour in the market, which raises the price to ten dollars per barrel, at a moment when money is worth two per cent a month? Or have those who had the control of money facilities combined to buy up all the wheat at moderate prices, with the design of speculating by a monopoly of one of the necessaries of life? Mechanicks and others have been indicted for combining to raise the price of labour; and it might be well to inquire whether combinations to raise the price of wood, pork, flour, and other necessities of life, beyond a fair profit, are not equally offences against society.

The foregoing is from the Albany Argus. The information it conveys in relation to the amount of the wheat crops is valuable. But the measure which it suggests for the purpose of reducing the price of flour is at utter variance with the principles of free trade, and with the natural rights of citizens. If mechanicks combine to raise the price of wages, they but hold forth an invitation to competition from beyond the sphere of combinations, and competition will soon arrange prices according to a just scale of equivalents. If merchants combine to raise the price of flour by purchasing all in the market, they but provoke competitors in foreign ports, whose rivalry will soon set matters right. The laissez nous faire maxim applies here as forcibly as in any other concern of trade. The true way is to leave trade to its own laws, as we leave water to the laws of nature; and both will be equally certain to find their proper level.

We already find that, incited by the high prices of bread stuffs here, foreign competitors are sending supplies across the ocean, and underselling our agriculturalists at their own doors. Part of the cargo of the Bristol, which was wrecked at Rockaway a fortnight ago, was English wheat; and we notice in the accounts of importation sin the newspapers that frequent mention is made of large quantities of foreign grain. Why is this? Why are prices so high in this country that the wheat growers of Europe can incur all the expenses of transportation, freight, insurance, commissions, and storage, and still undersell is in our own markets? Does the Argus really suppose that this result is brought about by a combination among the dealers in flour, “with the design of speculating by a monopoly of one of the necessaries of life?” The cause, let it rest assured, lies deeper than this. The monopoly is one of a worse character, or greater power, or more ruinous operation. Short crops may do something; combination may do something; but the high prices are mainly the result of the monopoly of banking. They are the natural and inevitable consequences of the wretched system which places the currency of the country completely under the control of the country completely under the control of a comparatively few specially privileged chartermongers, who avail themselves of the speculative disposition of the people to flood the country with a paper circulation, till the influx produces its natural effect of causing a vast depreciation of money, or appreciation of money prices, which is the same thing, and attracts competitors from all parts of the world to our market. These competitors do not take in payment, and carry away with them, the spurious currency which the monopoly banks have issued, but demand specie; and then comes the necessity of sudden retrenchment, followed by wide spread commercial distress. Prices then begin to fall; and at this point we are now arrived. Flour must soon go down, despite of all combinations, fancied or real; produce of all kinds must go down; rents must go down, and labour must go down; and all things must gradually adjust themselves to the retrenched state of the currency. When this period of depression is past, and the crops of the next year have paid up the deficit occasioned by overtrading during the present, the banks will begin to be liberal again, (munificent institutions!) and, urged on and stimulated by them, the people will act over again the same scenea of mad speculation, till the drama again concludes with a catastrophe of disastrous revulsion.

We should be glad if the Argus would turn its attention to the monopoly which is the true source of our high prices and our financial difficulties. It will find that our exclusive bank system is the cause of the evil, and the repeal of the restraining law the only effectual remedy.

THE SLAVE TRADE.

The British armed ship Vestal, of twenty-four guns, has recently captured, as we see stated in the newspapers, four slave vessels, three of which, sailing under Portuguese colours, were sent to Sierra Leone, and the fourth, a Spanish brig, called the Empress, to Havanna, where she arrived on the 25th of October. The Empress, when captured near the Island of Granada (one of the Caribee Islands) had on board four hundred and thirty-four slaves.

We see it also stated, in various English newspapers and other publications of late dates, that the detestable traffick in human beings is still carried on to a considerable extent, and with great openness, in the West Indies, and more especially in the port of Matanzas. Numerous ships from the United States are said to be sold there for the purpose of being convreted into slavers. Instead of purchasing Baltimore clippers and other fast sailing vessels, which have heretofore been procured for that horrid trade, those engaged in it now buy, it is said, leaky unsuspicious-looking ships, which are sent to the slave coast nominally for sperm oil, which, it seems, is only a sort of soubriquet for negroes. There is an anchorage ground near Matanzas, where the slave ships from the east coast of Africa are said to rendezvous, and where they land their slaves. They are thence marched to Matanzas, and put up for sale in the slave-market, under the very eyes of the authorities, who wink at this gross violation of the laws of nations.

If these facts are so, and we see no reason to doubt them, they show that the slave trade is carried on with a degree of openness and a sense of security that could not possibly exist, if the different governments of Christendom exercised anything like the proper vigilance and energy in their suppression of the dreadful traffick. We fear that our own government is exceedingly remiss on this subject.

LAMPLIGHT VERSUS MOONSHINE.

A report was adopted at one of the late meetings of the Board of Assistent Aldermen of this city, in favour of paying the lamplighters for every night in the year. The practice heretofore has been, we believe, to pay them for their services on those nights only when their services were actually rendered, and not to consider them entitled to wages for the gratuitous illumination of the moon. But moonshine and lamplight are hereafter to be on a par, and the citizens are to be taxed at the same rate for the one as for the other. “If Cæsar can hide the sun from us with a blanket, or put the moon in his pocket, we will pay him tribute for light,” was the boastful speech of Cloten, in Cymbeline. But our Common Council can do greater things than Cæsar; and though they have not yet altogether accomplished the feat of putting the moon in their pockets, they have performed what Cloten thought more difficult, and made us pay tribute for its light. What a glorious sinecure the lamplighters would have of it, if the Common Council would but extend their kindness a little further, and ordain that the moon shall shine every night of the year!

[5] THE LITERARY PLAINDEALER.

The Poor Rich Man and the Rich Poor Man. By the author of “Hope Leslie,” “The Linwoods,” &c. New York, Harpers & Brothers. 1836.

Miss Sedwick (it gives us pleasure to place her name the first word of the first article in this department of our paper) has given another proof, in the excellent little volume before us, of those kindly feelings and sympathies which seem to prompt her in all she writes. Her productions are always attempered by a fine philosophy. They breathe a most cheerful and encouraging tone, and glow with that quality which has been well termed the sunshine of the heart. They create in the reader the temper in which they seem to have been composed, and diffuse over his mind a delicious serenity, which it is the ambition of most authors of fiction wholly to dispel by what is commonly called powerful writing. Miss Sedwick is one of the very few writers of novels who seem always to keep in mind that the noblest office of fiction is to be the handmaid of truth. She aims at a higher purpose than merely to supply the idler with the means of agreeably dissipating an hour. She aims to his heart, to arouse his faculties, and to direct his mind both by example, in the incidents of her graceful narratives, and by precept, in the lessons of wisdom which those incidents suggest. We rise from the perusal of ordinary novels with a feeling somewhat akin to vexation that we have suffered the author to trifle with us, and to allure us to a chase in which we have wasted our time, pursuing phantoms which were not worth our sympathy. But we never peruse one of Miss Sedwick’s books that we do not feel wiser and better for what we read. They are full of practical good sense. They are the fruits of a mind which observes closely and reasons soundly, and which is governed by a high humanity—by a comprehensive philanthropy, that estimates its success rather from the good it does than the applause it wins.

The volume now before us is marked on every page with the peculiar impress of Miss Sedwick’s genius. The leading purpose of the work is denoted by its title, and to this purpose the author bends all her various powers: her nice discrimination of character, her talent in depicting manners, her singular felicity in colloquial writing, and all the resources of her wit and judgment. The incidents of her story are drawn from real life, and if they never happened in precisely the same combination, yet they are separately happening before our eyes every day. Her characters, too, are painted from nature, and are faithful portraits of persons who exist in every community. Indeed, one of the main charms of her story consists in its exact fidelity. The writer was too conscious of the affluence of her intellectual resources to feel any need of common clap-traps to catch the applause of common minds. It was not necessary to introduce demigods or devils into her story to ensure its being perused; nor to involve her principal persons in inextricable complications of adventure in order to provoke the interest of the reader. She has given them the common proportions of virtue and failings, she has led them through ordinary events, and subjected them to ordinary vicissitudes. The charm of the work consists in the nice delineation of delicately contrasted characters, in the graceful style of the narrative, the benevolence of its general tone and spirit, and the admirable force with which it illustrates the great moral truths which it was its object to inculcate—that wealth and poverty are misapplied terms when they have relation to mere outward conditions; that the source of true affluence is a well regulated mind; and that happiness is most surely found in useful and virtuous occupation.

There is another distinguished merit in this, as well as in some of Miss Sedwick’s previous productions, which we must not omit to name, because we should be glad to see her example emulated by other American writers. We allude to the American spirit which pervades it. By this phrase we would not have it supposed that any inflated compliments to American enterprise, or talent, or ingenuity, are intended. These things somewhat too much abound already in American books. We mean that sort of American spirit which leads her to shape the incidents of her story, the sentiments of her actors, and all the various circumstances of the fable, according to the actual conditions of things in this country, as they are modified by our political institutions. She selects her hero and heroine from humble life, and does not, in the end, find out that some trick had been played upon them in the cradle, and that they were not of “the lower orders,” but belonged of right to “the upper classes.” “Shame to us!” as Miss Sedwick indignantly observes, “that we do not abjure terms appropriate to our country.” She is actuated throughout by a truly democratick principle. She speaks of this as “a land where the government and institutions are the gospel principle of equal rights and equal privileges to all.” She does not admit that we have among us patricians or plebeians, or that honour and shame depend upon condition. She is the champion of the respectability of the virtuous poor, and teaches that honesty in rags is a thousand times more worthy of consideration, than wealth throned on his money-bags, and fenced round with exclusive immunities.

We have not room for a long extract from the Poor Rich Man and Rich Poor Man, but cannot refrain from copying at random a few pithy sayings which sparkle throughout its pages.

A little girl thus sweetly moralizes:

If you want to love people, or almost love them, just do them a kindness, think how you can set about to make them happier, and then love, or something that will answer the purpose, will be pretty sure to come.

The following are only a few of numerous apothegems which we marled with our pencil in the course of a hasty reperusal of tha story:

The benevolent principle is the true alchymy that converts lead to gold.

Education is the best capital for a young man to begin with.

The open hearted communicativeness of our people is often laughed at; but is it not a sign of a blameless life and social spirit?

A sound mind in a sound body will make almost a paradise of this rough-going world.

One cannot be very unhappy while there is enough to do.

Well may reflection be called an angel when it suggests duties, and calls into action principles strong enough to meet them.

A virtuous love is the greatest earthly security a young man can have against the temptations and dangers that beset him.

She receives the stranger with that expression of cheerful, sincere hospitality, which what is called high breeding only imitates.

Self-respect is the basis of good manners.

It is a comfort to the poor to feel that there is nothing low in poverty—to remember that the greatest, wisest, and best Being that ever appeared on earth had no part nor lot in the riches of this world; and that for our sakes he became poor.

We are tempted to extend our quotation of such passages to a much greater length; but the subjects which yet demand our time and space admonish us to close.

THE THEATRICAL PLAINDEALER.

Various considerations have induced us to appropriate a place in our columns to a weekly notice of the theatres. There are many readers who would be glad if that subject were wholly omitted; and an equal number, perhaps, who would like to see it made the chief topick of discussuion. We shall not attempt to accommodate ourselves to their opposite opinions; but shall pay precisely that degree of attention to theatrical matters which they may seem to us, from time to time, to deserve, and which may be requisite to make up the variety people naturally look for in a newspaper. Few persons, at the present day, are so ascetick as to disapprove of dramatick representations in themselves; but it is the abuses connected with the theatre which they condemn. These abuses, however, are not inherent in the drama, but are extraneous and adventitious; and bold, manly and well aimed criticism is therefore needed, since it may do much towards lopping off the supervenient excresences, and defacating the theatre of whatever is impure and unseemly. A Theatrical Plaindealer, actuated by a proper regard for the intrinsick excellences of the drama, and desirous only to eradicate what is exuberant, has a field before him in which he may achieve much good.

There is one abuse connected with the theatres which it is a matter of wonder that the force of publick opinion has not long since corrected. We allude to the facilities they furnish to women of the town, as such, to display their meretricious attractions, and spread their wiles, before the very faces of the chaster part of the audience. It was natural enough such violations of publick decency should be tolerated in the licentious days of Charles II. When the dramas of Congreve and Farquhar were the attraction of the stage, it was perfectly suitable that bawds and strumpets should form a part of the audience. But the times are changed, and so should be the practice of the theatres. We but touch upon this subject now; but it will receive hereafter our most particular attention and our most pointed rebuke.

Another custom, which is growing into fashion among us (though we well remember how it shocked the moral sense of [6] the community at first) is the exhibition of the licentious ballet. How gray-haired sires can take their daughters to the theatre, how husbands their wives, and brothers their sisters, and quietly sit with them to gaze and gloat on the voluptuous and lascivious exhibitions of the ballet, essentially demoralizing as such spectacles necessarily are in their nature and effect, is to us a matter of utter surprise. If the newspaper press were in the right hands, it would sound such a peal on this subject as could not fail to wake the publick sense of decency from the death-sleep into which it seems to have fallen. What we can do to rouse it from its lethargy shall not be withheld. [Online Editor’s Note: The author appears to have some odd hang-ups regarding displays of sexuality. While I do not share this strange position, and have no problem with overtly-sexual theatrical productions, my attitude toward the author is: to each his own, or to each her own, as the case may be.]

PARK THEATRE.

At the Park Theatre during the past week the Keeleys have been the principal attraction. The term which best characterizes the distinguishing merit of both these performers is neatness. Their excellence is not that of a very high order of histrionick genius, but of perfect finish of execution in what they attempt. Their acting does not thrill you with transport, or convulse you with mirth; but it produces a tranquil and equitable feeling of pleasure, an emotion not unlike that which is created by contemplating one of Wilkie’s pictures. They do not seek to make points; they lay no clap-traps to catch audien applause; but are content to gain the approbation of the judicious by the careful and just representation of every portion of a character. Every tone, every look, every gesture has been elaborately studied, and conned so well, that the traces of art str wholly concealed. As in poetry, the lines which seem, from the easy and natural turn of the thought and expression, to have flowed without effort from the writer’s pen, have commonly cost him the strictest and most patient revision; so in acting, the delicate and natural touches, which seem to spring spontaneously from the impulse of instant feeling, are generally the result of cool reflection, and diligent practice. But the ars est celare artem the Keeleys have in uncommon perfection. They are mechanical performers; but not of the Macready school: you do not see the wires and hear the clinking of the wheels.

Week after next we are to have Miss Ellen Tree; and in the course of her engagement Ion, a tragedy which has won, and in which she has won, great approbation from nearly all the criticks, certainly all the ablest, of the London press. Expectation is on tiptoe here to see both the actress and the play.

THE NATIONAL THEATRE.

Wallack in tragedy, and Hackett in his diversified line of native comedy, have been the alternate luminaries of this theatre for some time past. The former has produced Lord Byron’s drama of Sardanapalus, in the getting up of which the managers have spared no cost. It has been represented three times, during the past week, last night for Mr. Wallack’s benefit, when his personation of the voluptuous Assyrian monarch won the cordial applause of a numberous audience. Mr. Hackett has also brought forward a new piece, prepared for him by an experienced play-wright in London, and founded on the story of Horseshoe Robinson. Our engagements have not permitted us yet to witness the presentation of this drama; but if its merits as a play equal those of Mr. Hackett as a player, it will not fail to have a very successful run, not only in this city, but elsewhere. We should make that piece the subject of a more particular notice in our next number.

EDWIN FORREST.

The distinguished tragedian made his first appearance before a London audience at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, on Monday, the 17th of October, and was received by a very crowded house with the most enthusiastick applause. Private letters received in this city, as well as the London newspaper accounts, represent his success as complete. The part which was selected for his appearance was Spartacus, in the American tragedy of the Gladiator. The London Courier, a newspaper conducted with signal ability, and by no menas usually lavish of praise, speaks of Mr. Forrest in terms of the warmest. It says:

America has at length vindicated her capability of producing a native dramatist of the highest order, whose claims should be unequivocally acknowledged by the mother country; and has rendered back some portion of the dramatick debt so long due to us in return for the Cooks, the Keans, the Macreadys, the Knowleses, and the Kembles, whom she has, through a long series of years, seduced, at various times, to her shores—the so long dounted problem being happily solved by Mr. Edwin Forrest, the American tragedian, who made his his first appearance last night on these boards, with a success as triumphant as could have been desired by his most enthusiastick admirers on the other side of the Atlantick.

The incidents afford numerous striking situations and touching passages, all of which Mr. Forrest availed himself of with great tact, [word unknown], and effect; how astounding all eyes and ears by the overwhelming energy of his physical powers, and now subduing all hearts by the pathos of his voice, manner, and expression. The whole weight of the piece rests on him alone, and nobly does he sustain it. All the other characters are mere steps in the ladder, affording him successive elevations to mount up to the summit of masterly histronick delineation.

Mr. Forrest’s personal appearance is prepossessing in a remarkable degree. He is tall, handsome, muscular and admirably proportioned. Indeed we have no such figure on the stage. His legs are so totally unlike those spindle-shanks we are accustomed to see on our boards, as, at first sight, to appear padded and unnatural. He has well-defined regular features, and a dark vivid eye, replete with expressions. His voice is deep, powerful, and mellow. Its intonations are exceedingly flexible; and its slightest whisperings and mutterings can be distinctly heard all over the house. In his action there is great ease, gracefulness, and variety; and his declamation is perfectly free from the usual stage chaunt, catchings, and points. Indeed nature alone seems to have been his only model. If he has had any other view, we should say they were Kean and Talma, and more of the French than of the English Roscius. He is most certainly unlike any of our present actors. On the whole, we hail the appearanve of this gentleman as a new æra in the history of our stage, and look forward to his representations of the Shakspearian heroes with much interest, and with no apprehension.

The Mondon Morning Chronicle concludes a long and highly eulogistick notice of Mr. Forrest’s performance with the following remarks:

The whole weight of the tragedy thus rests upon the shoulders of Spartacus, and truly Mr. Forrest sustained it like an Atlas. Mr. Forrest is an exceedingly handsome man; tall, stout, and muscular, with strongly marked and regular features, and powerfully expressive eyes. His voice is deep-toned and mellow; sweet and touching in the expression of tenderness and grief, and yet capable of giving full effect to the wildest bursts of passion. In the level dialogue of the part he occasionally appeared somewhat declamatory and heavy; but this, we believe, was more owing to the matter itself than to his mode of delivering it; while he ever and anon absolutely electrified the audience by a beautiful trait of nature or feeling. During the whole of the last act, his performance was a blaze of splendour which has very rarely been equalled, and hardly ever, we should think, surpassed. His style appears to be very much his own. If he reminds us of any actor it is occasionally of Kean, especially in the rapid and conversational tone of many passages. Nothing could exceed the enthusiasm with which the audience expressed their sense of Mr. Forrest’s merit at the conclusion of the piece. He came forward after the fall of the curtain, and in a few words expressed his gratitute for the reception he had met with–a reception which, he said, would convince his countrymen of the kind feelings of the British nation towards America. This sentiment was warmly responded to by the audience.

The London Times devotes a column of its closest matter to a critique of Mr. Forrest, in which high praise is awarded to him. Among other things it says:

His voice is remarkably powerful, his figure rather vigourous than elegant, and his general appearance prepossessing. He played with the whole heart and seemed to be so strongly imbued with the spirit of the part, that every tone and gesture was perfectly natural, and full of that fire and spirit which are engendered by true feeling, and which more certainly than more graceful stage accomplishments carry an audience along with the performer. His fighting was admirable, and the postures into which he threw his herculean form in the conbat might form a study for sculptors.

The London Morning Herald, speaking of Mr. Forrest, says:

His action is full of variety and gracefulness, but at the same time, it partakes overmuch of the athletick style. There were several passages, not points, in Mr. Forrest’s performance in the Gladiator, which were exceedingly fine—the agony of generous grief, subduing the desire of vengeance, which he displays in the last act, where Spartacus hears of the death of his wife, and wishes to sacrifice the daughter of Crassus, or his brother, was expressed by him with a tremendous force, which reminded us above anything we have ever seen on the stagem of the head of the Loacoon, or Canova’s Hercules writhing under the tortures of the poisoned scarf. Mr. Forrest’s reception was such as his warmest riends could desire; it was enthusiastick in the extreme on his entrance; he was frequently applauded zealously during the performance, and at the end he was called before the curtain, and greeted with most prolonged cheering, and waving of hats and handkerchiefs from all parts of the house. More enthusiasm, in fact, we scarcely ever witnessed on the part of an audience in the British theatre.

As an evidemce of the sense entertained of Mr. Forrest’s merits behind the curtain, we may mention that, at the close of the performance, on the second representation of the Gladiator, the performers of Drury Lane Theatre, through Mr. Bartlet, presented him with a splendid snuff-box, of tortoise shell, lined and mounted with gold, with a mosaick lid, and the following inscription:

“To Edwin Forrest, Esq., the American tragedian, from the performers to the Theatre Royal Drury Lane, in testimony of their admiration of his talents as an actor, and their respect for him as a man, ‘His worth is warrant for his welcome hither.’”—SHAKSPEARE.

The foregoihg extracts occupy as much space as we can devote to this subject, and more than we should have done, were it not that Mr. Forrests’s unequalled professional and personal popularity gives much interest to whatever relates to his reception in London. All the London daily newspapers, and most of the weekly, speaj of him in very high terms of eulogy. The only two exceptions are the Examiner, which [7] is somewhat harsh in its criticism both of the play and players, but particularly of the former, and the Spectator, which is unjust.

ACCIDENTS, OFFENCES, &c.

LOSS OF THE SHIP BRISTOL.—This meloncholy disaster has, for the past week, been the chief topick of conversation. The Bristol lay off Sandy Hook at nine on Sunday morning, with the usual signal light flying for a pilot, but as none came out, she stoof off at eleven o’clock, the Highland Light then bearing N. N. W. At one o’clock the ship steered E. N. E. and at a quarter before four she struck on Rockaway about seven miles east of the Pavilion. The ship fell over, deck to the sea, and many of the steerage passangers were washed overboard. When the steerage passangers became acquainted with their situation, they rusjed on deck and were swept away by the waves almost as soon as they made their appearance. The wreck was discovered from the short early in the morning, but owing to the state of the weather, it was impossible to approach it, but about twelve o’clock on Monday [word(s) unknown] boat started and succeeded in reaching the wreck, from which she [word(s) unknown] eight or ten female passengers, and succeeded in landing them [word(s) unknown] on the beach. When the boat first started for the ship, she [word(s) unknown] tow line with her for the purpose of securing it to the ship [word(s) unknown] thus enabling them to make frequent trips to and from the [word(s) unknown] but it unfortunately proved too short, and they were [word(s) unknown] unable to return to the ship until twelve o’clock at night, when [word(s) unknown] survivors were taken off. Among them were the captain, [word(s) unknown] all the crew except the cook and steward, where were drowned [word(s) unknown] among the passengers lost was Mr. Donnelly, the son-in-law [word(s) unknown] late Michael Hogan, and he died a victim to his own [word(s) unknown]. Mrs. Hogan and two daughters, Mrs. Donnelly, her nurder [word(s) unknown] children were saved, and with other women and chilften, landed [word(s) unknown] the first boat. Twice the boats returned to the wreck, and [word(s) unknown] Mr. Donnelly yielded his place to others. In the third attempt to [word(s) unknown] the boats were swamped, and the crew became discouraged, and [word(s) unknown] not go back. Mean time the storm increased, and Mr. [word(s) unknown], with the two Mr. Charltons, took to the foremast, where the [word(s) unknown] many steerage passengers had sought temporary safety. [word(s) unknown], this mast soon went by the board, and of about twenty persons [word(s) unknown], Mr. Briscoe, a cabin passenger was saved, and he [word(s) unknown] at the bowsprit rigging, whence he was taken by the [word(s) unknown] captain and other cabin and steerage passengers, were on [word(s) unknown]-mast, and when that fell, he and others lashed themselves to [word(s) unknown], where for four hours the sea broke over them. [word(s) unknown] of the steerage passengers, principally women and children [word(s) unknown] almost immediately after the ship struck. Even before [word(s) unknown] leave their berths the ship bilged, filled, and all below were [word(s) unknown]. Not a groan was heard to denote the catastrophe–so awfully sudden was it. The ship has gone to pieces, and the cargo is totally [word(s) unknown]. The latter consisted of about 9000 bushels of wheat, a large [word(s) unknown] of railroad iron, dry goods, coal, &c. The ship was insured [word(s) unknown] $24,000, and most of the cargo was also covered by insurance. [word(s) unknown] of brokers of this city, soon after the above todings were [word(s) unknown], made, with prompt liberality a denotion of $900 for the relief [word(s) unknown] survivors from the wreck of the ship Bristol. The property saved amounys to less than $6000. Only seventeen bodies have drifted ashore, all of which have been decently interred. The Commercial Advertiser tells the following painful story concerning the fate of one of the passengers in the Bristol: Among the passengers in the wreck of the Bristol, was Mr. Christopher S., late of Paterson, and more recently of Brooklyn. Mr. S. was known to us. He left this country for Ireland, his native land, about four months since, on business, and was returning to his family in Brooklyn.&nsp; A few days before the wreck, Mr. S. had sent a letter to his wife by a vessel which they spoke. This letter she received the day before the wreck. It appears that Mr. S. had a young companion on board the ship, who in the moment of greatest peril, was below. He exerted himself greatly to save this young man, and succeeded. He remained himself on the wreck until his friend had gone on shore safe. He was among the last taken off, and, lamentable to state, when he was taken into the boat, his mind was gone! He was an idiot, and died very shortly after he was brought on shore. His friends whom he had saved, brought the intelligence to his family, consisting of a wife and three young children. The afflictive scene which followed, we will not attempt to describe.

FATAL STEAMBOAT ACCIDENT.—The Cincinnati Whig of the 18th ultimo relates the particulars of a fatal accident on board the steamboat Flora, while on her way from Louisville to Cincinnati, and within thirty miles of the latter place. The accident was occasioned by the sudden rapture of the pipes which connect the two boilers, the water from which, heated to the highest degree, ruskhed out in a torrent, and swept over the deck. The noise of the explosion startled the cabin passengers, and drew them in haste to the door, on opening which, the hot water poured in upon them, scalding one man to death and dreadfully injuring thirteen others, all cabin passengers, but one. The person killed was named Benjamin Myrick, of Charlestown, Massachusetts. Among those the most seriously and it is feared fatally injured, is the honorable G. L. Kinnard, member of Congress from Indiana. The accident is imputed to criminal negligence on the part of the engineer of the boat.

DISGRACEFUL ASSAULT ON A LADY.—On Tuesday afternoon, a respectable young lady went into the shoe store of Mr. Austin of No. 305 Broadway, and wished to purchase a pair of shoes. Mr. Austin, who is an old man, while assisting her in trying on the shoes, insulted her, the lady states, in a most shameful manner, the particulars of which delicacy forbids us to mention. The young lady screamed and flew out of the store as soon as she was able. Yesterday morning her brother, a young man of about twenty years of age, took a cowhide, and went to the store of Mr. Austin, on whom he inflicted a sound thrashing, to avenge the insult offered to his sister.

SINGULAR ROBBERY.—A few days since, two merchants from Pittsburgh, each bearing packages of money for Banks in Philadelphia, the one to the amount of sixty thousand dollars, and the other to the amount of twenty five thousand, travelled together about half the way to this city. At this point, the individual to whom the smaller sum had been entrusted, discovered that one of his [word(s) unknown] had been cut open, and that a package containing fifteen thousand dollars of the money had been stolen. He immediately offered a handsome reward for the recovery of the notes, and caused a negro [word(s) unknown] who was in the stage to be arrested on suspicion. The other passengers pursued their journey; but as nothing appeared on examination against the negro, an express pursued the stage to York, where [word(s) unknown] was made, and the lost money, $15,000, was found in the possession of the person to whose care the sixty thousand dollars had been committed, and who travelled in the company with his plunder [word(s) unknown] from Pittsburgh. This discovery created no little astonishment, and the offender was forthwith safely lodged in prison until [word(s) unknown] affair can undergo legal investigation.

AWFUL [WORD(S) UNKNOWN].—On Saturday evening last, Mrs. Vond, wife of Mr. James [word(s) unknown], residing on Sea street, Boston, went into the wood-shed with [word(s) unknown] in her hand, and while there fell down in a fit. Her clothes took fire, and before assistance arrived, she was so badly burnt [word(s) unknown] died in an hour.

STEAMBOAT ACCIDENT.—The steamboat Clouterville, from New Orleans to Natchitoches, struck a snag on the 3d ultimo, and immediately sunk. No lives were lost, and it is supposed that the cargo will be saved, but in a badly damaged state. The boat will be totally lost, with the exception of her engine and a portion of her furniture.

SUICIDE.—A man, residing in Thames street, Baltimore, named Brown, who had married a woman of that neighbouring about three months ago, and had since led with her a most unhappy life; went the other morning early into a tavern kept by a German named Blesky, where he asked for something to drink, and having obtained it, he laid down upon a bench in the bar room, and drawing a hat over his eyes, pulled a pistol from his pocket, and placing the muzzle against his head, discharged it. The result was a wound which instantly deprived him of life.

We have learned incidentally, with deep sorrow, the lamented death of Mrs. Chamberlain, wife of the Reverend J. Chamberlain, D. D. President of Claiborne county, Mississippi, about the 12th of October.—New Orleans Observer.

FRESHET IN JAMES RIVER, VIRGINIA.—There was a great freshnet in James River on Wednesday of last week. The tide was two or three feel above the wharves at Richmond.

DREADFUL DEATH.—Margaret Louisa Morris, aged 4 years, daughter of Mr. Samuel Morris, of this city, was burned to death on Saturday evening last, by her clothes accidentally taking fire.

DISTRESSING CASUALITY.—A young man, employed in the sash and blind manufactory of Messrs. Forbes, Bulow & Co., of New Haven, while performing some duty near the steam engine, got his roundabout jacket caught by a square revolving shaft, around which it was instantly so enveloped that he was unable to extricate himself, but was carried around with it at the rate of fifty revolutions to the minute, his limbs thrashing against a parallel beam above and below, till they were crushed in a most awful manner. One of his legs was amputated by Doctor Knight, and it is still doubtful whether the other can be preserved.

ROBBERY OF THE ONEIDA BANK.—On Saturday night the vaults of this Bank were entered, and one hundred and eighty thousand dollars stolen. The robber entered, as we understand, by means of false keys, by which he opened some half dozen locks, including that on the front door. But one lock was broken. The porter of the establishment examined the bar across the vault door, at 9 o’clock in the evening, and found all safe. He then went to bed, and did not leave the bank until Monday morning. We have not heard that any clue to the matter has yet been found, or that suspicion has as yet fastened upon any one. The money taken consisted of the bills of other banks: no specie was taken. This institution was expected to go into operation in a few days; but should the money not be recovered, it is doubtful whether it can proceed without an application to the Legislature. It is not often that in this community we have to record such an atrocious act of villainy as this one: yet in what respect is this robbery worse than some of the acts attending the incorporation of this very bank? Morally it is no more: and as it regards its effects upon publick virtue, not half so bad: and while we would lend every effort to detect, and bring to justice the thief, and while we deplore the loss to the bona fide holders of the stock, we have no sympathies for those who, by a breach of every obligation, have unjustly gorged large amounts of it, which should have been distributed otherwise. The thief might well challenge a comparison with the Bank Commissioners: he might say to them—“I have broken the law, it is true; you have done the same; but the law never reposed any special trust or confidence in me, and therefore I have betrayed none: you were charged with the execution of a trust, and the legislature relied upon your honour and honesty for a faithful discharge of it—you have proved false—you are more guilty than I.” We hope the money may yet be recovered, and we should not be surprised if the robber should be found to be some one of the confidants or dummies of the commissioners, or some of the vagabonds who have been allowed to prowl about the banking house since it has been occupied by the Oneida Bank.—Utica Democrat.

A MEETING HOUSE BURNT.—The new Methodist Meeting House in the town of Greenland, New Hampshire, was destroyed by a fire a few nights since.

GREAT FIRE AT JOHNSTOWN.—A disastrous fire occurred last Saturdat morning, in Johnstown, Montgomery county, in this state, by which the fairest portion of the village, including the Episcopal Church, was consumed. The value of the property is estimated at $30,000, of which there was insurance to the amount of about $15,000.

A “FAIR BUSINESS TRANSACTION.”—It may be recollected that Mr. Stevens, a jeweller in Dey street, wasa lately robed of $20,000 worth of Jewelry, and offered a reward of $4000 for the recovery of the property, or $5000 for the restoration of the property and detection of the robbers. He however, heard no more of the matter until a few nights back, when a person stopped him in the street, and told him that if he would call at a certain house the night after and pay $4000, his property would be restored to him. Mr. Stevens accordingly went to the appointed place a couple nights since, and paid the $4000, and was then given back his $20,000 worth of jewelry.—Journal of Commerce.

[8] A BIT OF A MISTAKE.—The other day, a passenger on board of one of Canal swift-boats missed his handkerchief, and, suspecting the honesty of a genuine son of the sod who sat next him, he bluntly requested him to unfold the secret of his roguery, by submitting himself to be searched. At once, with great good will, the scrutiny was consented to, but it turned out most awkwardly for Paddy’s accuser, that the missing article was at last discovered in his own hat. The latter, of course, proceeded in all haste to apologize for his mistake, when he was interrupted by Paddy replying, not in a lady’s whisper, “O never mind, there is no harm at all, at all; you took me for a rogue, and I took you for a jintleman, and now you see we were both mistaken!”

HYDROPHOBIA.—The Connecticut Courier related a case of hydrophobia which ended in death last week at Hardford [word(s) unknown] coloured man, named George, living with a Mr. Kempton, was [word(s) unknown] on the thumb, about five or six weeks ago, in attempting to confine [word(s) unknown] dog. The wound healed, and little was thought of it until about two days before his death. It was then observed by one of the family that [word(s) unknown] could not, or did not drink his tea at night. This alarmed the family, and steps were taken to ascertain the state of his case, when it was [word(s) unknown] that he could not possibly swallow any liquid, and that the mere [word(s) unknown] of it, or even the pouring of it from one vessel into another, threw [word(s) unknown] into spasms. The spasms, which affected the whole region of the [word(s) unknown] but were most painful and severe about the pit of the stomach, were found the next morning to give him great agony, coming on every few minutes spontaneously, and being excited at any moment by offering him drink. They increased during the day, and finally terminated in death about ten o’clock, Thursday evening. During the last day, however, by great effort, he succeeded in swallowing a cup of warm water, which was immediately ejected; and this was the only fluid taken

ALTERED BANK NOTES.—Five dollar notes of the Commercial Bank of Pennsylvania, and of the Mechanick’s Bank of Philadelphia, neatly altered to fifties, are in circulation.

A TURN-OUT.—Seventy students of the University of Virginia at Charlottsville were expected a fortnight ago, in consequence of a military epidemick which had broken out among them, and which exhibited itself in a sundry bellicose symptoms. The young men were resolved to organise themselves into a military company, assume a military dress and equipments, and devote a large portion of their time to military avocations. The faculty, on the other hand, determined that they should wear the academic toga, submit to college discipline, and devote their hours to peaceful studies. They had but one alternative allowed them—obedience or expulsion. Not choosing to yield obedience, they have been expelled.

KIDNAPPING IN THE NORTH.—The Exeter News Letter, reports the examination before a Justice, on complaint of an Observer of the poor, of Noah Rollins, in Sanberton, charged with enticing, kidnapping, and stealing Benjamin Sweet, a mulatto boy, under 10 years of age, and selling him for ten dollars to Samuel Bennett, with the intent of conveying him away out of the State, to the State of Alabama, and to hold him in slavery during his life. It appeared in evidence that the overseers of the poor, in February, 1835, let Rollins take the boy from the poorhouse, to keep a year on trial. At the end of that time he was to take him on indentures, until twenty-one years old, or return him; but the boy had never been returned until he was brought back last October. Rollins sold the boy to Bennett—who resides in Alabama, but was on a visit to his brother at Northwood—for fifty dollars, which fifty dollars was repaid when the overseers took home the boy, and the next day Bennett cleared for Alabama. Rollins offered no evidence, but contended that no offence was proved which should subject him to the cognizance of the laws of that state. The justice, however, ordered him to recognize in the sum of $500, for his appearance at the Court Common Pleas, and for want of sureties he was committed.

THEATRE.

THIS EVENING, first night of LA BAYADERE, as originally produced in Paris. To aid the effect of this Melo Dramatick operatick Ballet, engagements have been entered into, for limited periods, with M’lle Augusta, Miss Cowan, and Miss Kerr. Zoloe, M’lle Augusta; Fatima, Miss Kerr; Ninka, Miss Eveline Cowan. Previous to the Operatick Ballet, the Farce of HOUSE ROOM; and the performances to conclude with the MARRIED RAKE.

MR. & MRS. KEELEY’S nights next week will be Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday and Thursday.

FRIDAY, Mr. Keeley’s Benefit.

T H E P L A I N D E A L E R.

NEW YORK, DECEMBER 3, 1836.

Paris papers to the evening of October the 25th, have been received. Their contents are not of importance. The affairs of Spain continue in an exceedingly unsettled state. Mendizabel, the Minister of Finance, has offered orders upon the revenue of Cuba, in payment of the new instalments of interest due upon the foreign debt of the kingdom, and this has given great dissatisfaction on the Exchange of Paris. Some of the French creditors had taken measures to attach Spanish government funds in the hands of Paris bankers. The French government, it is said, would also insist, that M. Mendizabel, should preserve good faith with the foreign creditors. It was stated on change of the 21st, that a great number of the holders of Spanish bonds had resolved to protest against the mode of payment just adopted by the Queen’s government. This protest, it was added, was to be delivered on the following day to the Spanish Ambassador.

The affairs of Spain seem to occupy the attention of all the cabinets of Europe. An interview between the Emperours of Russia and Austria, the King of Prussia, is spoken of, to take place early in December, somewhere in Silesia. The object is said to be to unite in some course respecting the affairs of Apain, and of Belgium.