Platforms

During the colonial era of American history, what would eventually become these united states were at the time under the thumb of the British king. Indeed, most colonists in the early days saw themselves as British citizens or subjects. The parties that existed then were the British parties, the Whigs on the left and the Tories on the right. While Cato’s Letters were not official documents of the Whig party, they were reprinted often in the American colonies and helped to cultivate a revolutionary liberal outlook on the American side of the pond.

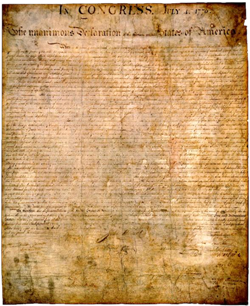

The Declaration of Independence

1776 — Two unofficial parties existed in the American colonies during the 1770s: the patriots on the left, who wanted to secede from England, and the loyalists on the right, who didn’t. While these parties had no platforms, the Declaration of Independence, drafted by the radical liberal Thomas Jefferson, serves as a poignant representation of the views shared by many of these revolutionaries.

1787 — Debate mounted, following the noble rebellion in Massachusetts, over whether we should have a stronger centralised state. While the federalists on the right wanted to see the newly-written Constitution ratified, thereby strengthening the power of the centralised state at the expense of the people, the anti-federalists on the left feared that adoption of the Constitution would only end in tyranny. (History has proved these liberal republicans correct.) Since neither was yet an official party, neither had a platform per se; yet, the letters written by various authors and collected under the name Antifederalist Papers could be regarded as an unofficial platform of this leftist resistance.

The Kentucky and Virginia Resolves

1798 — As the Hamiltonian conservatives were concentrating power using the Federalist party as their vehicle, the Jeffersonian liberals formed an opposition party based on republican values. Following the despicable Alien and Sedition Acts of the Adams administration, James Madison and Thomas Jefferson, central figures in the newly-established Republican party, authored the Kentucky and Virginia Resolves defending nullification of unconstitutional laws. While the liberals opposed the adoption of the Constitution a decade earlier, their attitude settled on the position that, so long as we are stuck with the U. S. Constitution, let us at least not expand the scope of centralised power beyond that permitted by the selfsame document. While the Kentucky and Virginia Resolves were not official platform positions of the Republicans, the resolves did announce the “Principles of 1798,” which became the hallmark of the party.

1800 — The Republican party’s 1800 platform, written by Thomas Jefferson, became the first official party platform in these united states. The party never held a national convention, but rather named candidates and adopted platforms through its congressional caucus. The nationalistic Federalist party on the right had no platform at this time, although there were well-known reports written by the proto-fascist Alexander Hamilton concerning his mercantilist economic agenda.

The Republican Party Under Jefferson

1801–1809 — Unfortunately, Jefferson was not as liberal in office as he was out of office. In his letters, Jefferson expresses a nearly-anarchist outlook. But, in office, he committed a number of acts that are to be condemned, including the unconstitutional Louisiana Purchase, and the unconstitutional war he waged. While I would maintain that Jefferson was one of the three greatest presidents that these united states have, following the Philadelphia Convention, ever had, this fact only goes to show how abysmal most presidents are. No new political platforms were issued during this time.

The Republican Party Under Madison

1809–1817 — Under the administration of the moderate Republican James Madison, many Federalists united with the Republicans, shifting the party’s orientation uncomfortably rightward. James Madison was even less liberal than Jefferson, and it was under Madison that the unnecessary War of 1812 occurred. According to Cuthbert Vincent, “Under Madison’s administration the Federalists of the United States largely united with the Democrats, the war of 1812 engrossed the people’s attention and party lines were badly shattered. With the election of Jefferson in 1800 the difference between the parties had been practically wiped out, there being no further reason for the party of power to denounce usurpations of authority and charge infraction of constitutional rights, nor reason for those out of power to urge a right to the exercise of greater authority by the administration.”

The Hartford Resolutions

1815 — There was a tiny contingent of liberals within the Federalist Party, however, that did wish to challenge the President. On 4 January 1815, they issued the Hardfort Resolutions, which called for strict limits on the war powers. According to Vincent, these resolutions “served rather to promote the annihilation of the party.” The Federalists would only nominate one more candidate for president, Rufus King, in 1816.

The Democratic Republican Party After Madison

1817–1836 — As was noted above, the Republican Party’s orientation shifted uncomfortably rightward as a result of the influx of former Federalists into the party during the administration of the moderate James Madison. Thus, Presidents James Monroe and John Quincy Adams were both clearly conservative in orientation.

Luckily, there were still liberal elements within the Democratic Republican Party. The Jacksonians tended to be on the liberal wing of the Democratic Republican Party, and historian Thomas J. DiLorenzo describes Martin Van Buren (the man predominately responsible for building the Democratic Party of Andrew Jackson) as “one of the most libertarian statesmen in American history.” (Unfortunately, Andrew Jackson himself was not nearly as libertarian as his wing of his party; thus, Jackson enforced Henry Clay’s Tariff of Abominations, and committed his own atrocities with the “Trail of Tears.”)

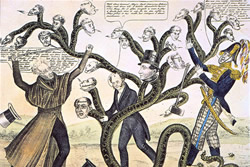

The main issue in the 1832 U. S. election was the Second Bank of the United States. The conservatives were in favour of centralised banking, and the liberals were against it. As DiLorenzo notes on page sixty-nine of his Hamilton’s Curse, Jackson, upon taking office in March three years earlier, explained that the Bank of the United States was “a monster, a hydra-headed monster…equipped with horns, hoofs, and tail so dangerous that it impaired the morals of our people, corrupted our statesmen, and threatened our liberty. It bought up members of Congress by the Dozen…subverted the electoral process, and sought to destroy our republican institutions.”

When the Jacksonians held their first national convention in 1832, they were still calling themselves the Republican Party. By the mid-1830s, they were referring to themselves as the Democratic Party, although the term “Democratic Republicans” was also often used. The party has been officially calling itself the Democratic Party ever since 1844.

The National Republicans

1828–1836 — Some of the nationalists within the Democratic Republican Party had split, in 1828, to form the National Republican Party, a party which fortunately did not succeed in taking the presidency. On 11 May 1832, the nominating convention in Washington, D. C., issued a ten-point platform enumerating aspects of Henry Clay’s so-called “American system.” These included protectionism, mercantilism, nationalism, so-called “internal improvements,”—basically, this was a continuation of the Hamiltonian agenda. These nationalists were particularly annoyed that President Andrew Jackson had vetoed the renewal of the unconstitutional national bank. By 1836, the National Republicans merged into the newly formed Whig Party, which it must be noted was the conservative party of its day, unlike the British Whigs who had been the liberals to the Tory conservatives.

Despite the creation of a new conservative party, there were still conservative elements within the Democratic Party.

1836 — The Locofocos were a radical faction of the Democratic Party that existed in the mid-1830s. In 1836, they split from the Democratic Party’s conservative elements to form their own radically liberal party: the Equal Rights Party. According to Wikipedia, this new party “contained a mixture of anti-Tammany Democrats and labor union veterans of the Working Men’s Party. They were vigorous advocates of laissez-faire and opponents of monopoly. Their leading intellectual was libertarian editorial writer William Leggett.” This declaration was drafted by Moses Jacques.

The Democratic Party Under Van Buren

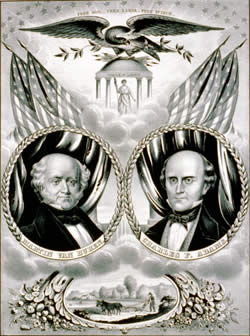

1837–1841 — The architect of the Democratic Party became president after Jackson. Historian Jeffrey Rogers Hummel describes Van Buren as “the greatest president in American history,” a position with which I agree. Many of the Locofocos reaffiliated with the Democratic Party during the Van Buren administration, and William Leggett would have become the American minister to Guatemala under Van Buren had he not unfortunately died on 29 May 1839.

Unfortunately, in his inaugural address, Van Buren explicitly says he will not work to abolish slavery—a position that, rightly, annoyed the libertarians and other abolitionists.

1839 — The American Anti-Slavery Society was an abolitionist society formed by the libertarian William Lloyd Garrison in 1833. Libertarianism first began coalescing as an actual movement in the 1830s, having been born in the broader abolitionist movement. In a convention on 13 November 1839, in Warsaw, N. Y., a number of abolitionists met to organise an openly-abolitionist political party, which would eventually call itself the Liberty Party. Garrison, being a radical, did not think it wise to fight the system from the inside; hence, it can be said that the Liberty Party split from the American Anti-Slavery Society, and aimed to fight slavery through the political process. Along with the Equal Rights Party, the Liberty Party was one of the first officially-organised libertarian parties in these united states. The Liberty Party held its first national convention in Albany, N. Y., on 1 April 1840.

1840 — This platform generally follows in the radical liberal tradition of Jefferson, except for one glaring instance. In the seventh clause, the party presents a confused—and, needless to say, disgusting—defence of slavery. This defence seems extremely out-of-place in this otherwise radically liberal document. 1840 is the year the Democratic Party nominated for reelection the liberal Martin Van Buren, who would later leave the Democratic Party and join up with other “Barnburners” as well as members of the Liberty Party to form the abolitionist Free Soil Party. Unfortunately, Van Buren lost in 1840 to the Whig candidate, William H. Harrison.

The Election of 1840

1840 — According to the libertarian Murray N. Rothbard, “The Jacksonian libertarians had a plan: it was to be eight years of Andrew Jackson as president, to be followed by eight years of Van Buren, then eight years of [Thomas Hart] Benton. After twenty-four years of a triumphant Jacksonian Democracy, the Menckenian virtually no-government ideal was to have been achieved. It was by no means an impossible dream, since it was clear that the Democratic party had quickly become the normal majority party in the country. The mass of the people were enlisted in the libertarian cause. Jackson had his eight years, which destroyed the central bank and retired the public debt, and Van Buren had four, which separated the federal government from the banking system. But the 1840 election was an anomaly, as Van Buren was defeated by an unprecedentedly demagogic campaign engineered by the first great modern campaign chairman, Thurlow Weed, who pioneered in all the campaign frills—catchy slogans, buttons, songs, parades, etc.—with which we are now familiar. Weed’s tactics put in office the egregious and unknown Whig, General William Henry Harrison, but this was clearly a fluke; in 1844, the Democrats would be prepared to counter with the same campaign tactics, and they were clearly slated to recapture the presidency that year. Van Buren, of course, was supposed to resume the triumphal Jacksonian march. But then a fateful event occurred: the Democratic party was sundered on the critical issue of slavery, or rather the expansion of slavery into a new territory. Van Buren’s easy renomination foundered on a split within the ranks of the Democracy over the admission to the Union of the republic of Texas as a slave state; Van Buren was opposed, Jackson in favor, and this split symbolized the wider sectional rift within the Democratic party. Slavery, the grave antilibertarian flaw in the libertarianism of the Democratic program, had arisen to wreck the party and its libertarianism completely” (For a New Liberty: The Libertarian Manifesto, pp. 9–10).

Why was Van Buren defeated? One reason might be, as David C. Whitney puts it, the Whigs “portrayed him as a ‘lily-fingered aristocrat’ who drank wine from a silver cooler and ate his meals from gold plates. … On the other hand, they featured their candidate, Harrison, as a man of the people who could live in a log cabin and be content with hard cider. Although the facts were that Harrison was born in a mansion as a Virginia aristocrat and Van Buren was the self-made son of a tavern keeper, the voters believed the Whig version and Van Buren was defeated” (The American Presidents, 9th ed., p. 82).

With the election of Harrison, things looked bleak. DiLorenzo writes, “After the 1840 election, when the Whigs controlled both houses of Congress as well as the White House, Clay surely must have thought that the entire ‘American System’ would finally be rubber-stamped. It probably would have been, too, except that the Whig president, William Henry Harrison, died one month after being inaugurated. His successor, John Tyler, turned out to be a…Jeffersonian who opposed the entire Hamiltonian scheme. President Tyler vetoed a Clay-sponsored bill to resurrect the Bank of the United States and opposed his protectionist tariffs and corporate welfare schemes as well. The Whigs exploded in anger, burning Tyler in effigy in front of the White House and kicking him out of their party” (p. 121).

1843 — A few years later, the Liberty Party was back, this time with a political platform detailing its abolitionist agenda. Although the party claims, in its fourth plank, not to be a single-issue party, the entire platform deals primarily with the issue of slavery, save perhaps for clause sixteen which supports “freedom of speech and of the press, and the right of petition, and the right of trial by jury.” The convention was held in Buffalo, N. Y., on 30 August 1843. 148 delegates were present, representing twelve states.

Democratic Platform of 1844

1844 — Unfortunately, it seems the Democratic Party went downhill following the 1840 election. In 1844, the Democratic Party nominated the pro-slavery Democrat James K. Polk for president, and added a nationalistic plank to its platform. While the 1844 platform declared the party to be still dedicated to the nine principles listed in its 1840 platform, it added to this three new positions, including the nationalist position in favour of admitting Texas and the Oregon Country into the union. (The Whig Party, interestingly, took the liberal position with regards to Texas, opposing the annexation, although said opposition did not find its way into their nationalistic platform.) Fortunately, at least the other two new Democratic planks were liberal: the platform defended the presidential veto, and maintained that the proceeds from the sale of public lands should be applied solely to objectives that are constitutional.

The Liberty Party in 1847

1847 — According to the Gerrit Smith faction of the Liberty Party, some allegedly non-abolitionist elements within the party (the Salmon P. Chase faction), attempted to hold a Liberty Party convention in 1847, with the objective (allegedly) of making the party appear more “moderate” in its opposition to slavery, and in order to nominate for the presidency Senator John P. Hale of New Hampshire. This extremely annoyed the Smith faction within the party, who in 1848, held another convention in order to “re-radicalise” the party and nominate none other than Gerrit Smith, himself, in Hale’s place. At least, this is the account of those Liberty Party members who remained in the party in 1848; another interpretation I found is that the Chase faction wanted to keep the party from moving in a puritanical direction, which it eventually did anyway. In any event, the Chase faction went on to form the abolitionist Free Soil Party, which nominated the liberal former president, Martin Van Buren.

The Election of 1848

1848 — With the election of 1848, both the Democratic and Whig Parties continue to slide, or perhaps slither, downhill, and away from any noble principles. In 1848, the Democratic Party nominated the disgusting Lewis Cass. In protest, many antislavery Democrats walked out of the Baltimore convention to instead support the Free Soil Party. Also that year, the party again amended its platform, adding to it a despicable defence of the Mexican–American War—the same Mexican–American War that Henry David Thoreau called “the work of comparatively a few individuals using the standing government as their tool; for, in the outset, the people would not have consented to this measure,” in his sublime essay, “Civil Disobedience.” Meanwhile, the Whig Party nominated the conservative Zachary Taylor for president, and issued a platform that was little more than mindless applause for their war-hero candidate. The Whigs won, clearly indicating that the pro-slavery wing of the Democratic Party had not been as all-encompassing as the Democratic establishment had hoped. There were simply too many antislavery Democrats (or “Barnburners,” as they were called) attracted to Van Buren’s campaign for the Democratic Party to obtain victory.

1848 — While the platform of ’43 was, as was noted above, largely a single-issue party, the platform of ’48 adopted a number of positions, some of which were libertarian (such as fervent opposition to slavery, opposition to the Mexican–American War, and opposition to tariffs) and some of which also tended toward being illiberal and unlibertarian. The most clearly antilibertarian position it adopted was support for the prohibition of transferring alcohol. The party also called for land reform, which may or may not be libertarian depending upon various factors, and claimed to be against secret societies. Thus, while I regard the party of ’43 a libertarian party, I regard the party of ’48 as, at best, a liberal party, and at worse, a conservative one.

1848 — It can be debated whether the Free Soil Party was an abolitionist party or merely an antislavery party. Those who remained in the Liberty Party following 1848, for example, would likely claim that the Free Soil Party was merely an antislavery party, and not truly an abolitionist party, because the Free Soil Party didn’t happen to believe that the U. S. Congress had the power to abolish slavery without the aid of a constitutional amendment. Nevertheless, most of the members of the Free Soil Party would have likely regarded themselves as abolitionists, for surely their preference would be to see slavery abolished in every state of the Union, and without delay; and surely its state affiliate parties would have recognised that as a goal of their state parties. Because of this, I, for one, and for what it’s worth, am willing to regard the Free Soil Party as an abolitionist party, despite the fact that the party’s rhetoric was often subpar. Moreover, I am willing to grant it the distinct honour of being described as America’s third libertarian party, the first two of course being the Equal Rights Party of 1836 and the second being the Liberty Party of 1843.

In 1848, the Free Soil presidential candidate, the liberal Martin Van Buren, took over ten percent of the vote. It was from this election that the term “spoiler” arose, as the Democrats were calling the Free Soilers “Free Spoilers” for allegedly taking votes away from the Democratic Party. Of course, Free Soilers could easily retort that if the Democrats had wanted their votes, they wouldn’t have nominated the despicable Lewis Cass.

The Whig Party After 1848

1849—1853 — Whig candidate Zachary Taylor won, and as president, continued the conservative agenda of big government interventionism, corporate welfare, and protectionism. When Taylor died, the pro-slavery Millard Fillmore took his place and signed into law the big-government—indeed, the fascistic—Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. The Fugitive Slave Act had been part of the Compromise of 1850, which the abolitionists correctly recognised seemed to be a series of concessions to the Slave Power.

1849 — Again, one year later, the party opts to advocate a variety of good positions along, unfortunately, with a variety of tyrannical ones. One very interesting fact, however, is that in clause 22, the party officially endorses a book by the radical libertarian Lysander Spooner. While the platform does not give the title of the book being endorsed, it is unlikely to be any other than The Unconstitutionality of Slavery (1845).

1852 — Interestingly, the party opted to drastically cut back it platform in 1852, allowing only four planks to remain. Here, the party retains its libertarian support for abolition of slavery and its right-wing support for alcohol prohibition.

The Rebellious Stripes Flag, adopted by the Sons of Liberty in 1767

The Gadsden Flag was adopted by various American revolutionaries in 1775

The Declaration of Independence

Ratified 4 July 1776Portrait of Thomas Jefferson (1800)

by Rembrandt PealeGeneral Jackson Slaying

the Many Headed Monster (1836)

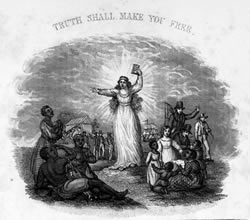

N. Y.: Printed & publd. by H. R. Robinson“The Truth Shall Set You Free,” Frontispiece for The Liberty Bell, by Friends of Freedom (Boston: For the Massachusetts

Anti-Slavery Fair, 1839).The 1848 Free Soil campaign banner

The Libersign, adopted in 1972 as the first emblem of the Libertarian Party

This was the symbol of the Libertarian Party for many years

Some state-level Libertarian Parties

in the united states have adopted

“LP the Liberty Panguin” as their mascot

in place of Lady LibertyThe current symbol of the Libertarian Party