The Liberty Party

1839 — The American Anti-Slavery Society was an abolitionist society formed by the libertarian William Lloyd Garrison in 1833. Libertarianism first began coalescing as an actual movement in the 1830s, having been born in the broader abolitionist movement. In a convention on 13 November 1839, in Warsaw, N. Y., a number of abolitionists met to organise an explicitely-abolitionist political party, which would eventually call itself the Liberty Party. Garrison, being a radical, did not think it wise to fight the system from the inside; hence, it can be said that the Liberty Party split from the American Anti-Slavery Society, and aimed to fight slavery through the political process. Along with the Equal Rights Party, the Liberty Party was one of the first officially-organised libertarian parties in the united states. The Liberty Party held its first national convention in Arcade, N. Y., on 1 April 1840. For the office of president of the united states, it nominated James G. Birney as its candidate.

1843 — Four years later, the Liberty Party was back, this time with a political platform detailing its abolitionist agenda. In this platform, the party claims not to be a third party or a new party, but rather the party of 1776. Although the party claims, in its fourth plank, not to be a single-issue party, the entire platform deals primarily with the issue of slavery, save perhaps for clause sixteen which supports “freedom of speech and of the press, and the right of petition, and the right of trial by jury.” The abolitionist Salmon P. Chase was instrumental in the adoption of this platform. The convention was held in Buffalo, N. Y., on 30 August 1843. 148 delegates were present, representing twelve states. The party again nominated James G. Birney for president.

Report from the County of Madison: To Abolitionists

1843 — A letter from Gerrit Smith to the abolitionists of Madison County, N. Y., published on 13 November 1843, explaining that they had fought the good fight, and predicting that the party would make even more progress in the next election.

The Address of the Southern and Western Liberty Convention

1845 — A speech, written by Salmon P. Chase, was delivered in 1845. It contains not only Chase’s arguments that slavery is inherently unconstitutional in all federally-controlled territories, and in all states added to the union following the revolution, but also an impassioned call for the people of slave-states to immediately abolish slavery within their states. This speech is remarkable in its depiction of the major parties of his day: The Democratic Party was an excellent instrument in most regards, save the vital issue of slavery; and the Whig Party at best paid lip service to antislavery concerns, never wishing to actually divorce itself from the slave power. Most of the abolitionist Democrats he brought into the party would follow Chase into the Free Soil Party three years later.

In one forceful paragraph, Chase explains that slavery is “the complete and absolute subjection of one person to the control and disposal of another person, by legalized force. We need not argue that no person can be, rightfully, compelled to submit to such control and disposal. All such subjection must originate in force; and, private force not being strong enough to accomplish the purpose, public force, in the form of law, must lend its aid. The Government comes to the help of the individual slaveholder, and punishes resistance to his will, and compels submission. THE GOVERNMENT, therefore, in the case of every individual slave, is THE REAL ENSLAVER, depriving each person enslaved of all liberty and all property, and all that makes life dear, without imputation of crime or any legal process whatsoever. This is precisely what the Government of the United States is forbidden to do by the Constitution. The Government of the United States, therefore, cannot create or continue the relation of master and slave. Nor can that relation be created or continued in any place, district, or territory, over which the jurisdiction of the National Government is exclusive; for slavery cannot subsist a moment after the support of the public force has been withdrawn.”

The Unconstitutionality of Slavery by Lysander Spooner

1845 — This provocative legal defence by the libertarian Lysander Spooner’s of the abolitionist position, which was based on a literal reading of the U. S. Constitution, was endorsed by the Liberty Party in the twenty-second plank of its 1849 platform. Spooner’s book was so influential, in fact, that it convinced the former slave Frederick Douglass that the Constitution was, properly understood, an antislavery document. Previously, Douglass had agreed with the Garrisonian view that the Constitution was a pro-slavery document and, therefore, a pact with the Hell. In an 1851 address to the voters of the united states, Gerrit Smith writes that “the few, who have, of late, acted with the Liberty Party, do all hold with the highly intellectual Lysander Spooner and with other writers, that, according to the well settled and universally received canon of interpretation, an antislavery, instead of a proslavery, construction is the only one, that can possibly be given to the Federal Constitution.”

1846 — A letter from Gerrit Smith to his party, dated 7 May 1846, urging them not to extend their platform beyond the issue of abolitionism. A little over a year later, in a letter to the editors of The Emancipator, Smith would take the exact opposite position on the question of whether to add other issues to the Liberty Party platform.

The Liberty Party in 1847

1847 — According to the Gerrit Smith faction of the Liberty Party, some allegedly non-abolitionist elements within the party (the Salmon P. Chase faction), attempted to hold a Liberty Party convention in 1847, with the objective (allegedly) of making the party appear more “moderate” in its opposition to slavery, and in order to nominate for the presidency Senator John P. Hale of New Hampshire. This extremely annoyed the Smith faction within the party, who in 1848, held another convention in order to “re-radicalise” the party and nominate none other than Gerrit Smith, himself, in Hale’s place. At least, this is the account of those Liberty Party members who remained in the party in 1848; another interpretation I found is that the Chase faction wanted to keep the party from moving in a puritanical direction, which it eventually did anyway. In any event, the Chase faction went on to form the abolitionist Free Soil Party, which nominated the liberal former president, Martin Van Buren.

1848 — While the platform of ’43 was, as was noted above, largely a single-issue platform, the platform of ’48 adopted a number of positions, some of which were libertarian (such as fervent opposition to slavery, opposition to the Mexican–American War, and opposition to tariffs) and some of which also tended toward being illiberal and unlibertarian. The most clearly illiberal position it adopted was support for the prohibition of transferring alcohol. The party also calls for land reform, which may or may not be libertarian depending upon various factors, and claimed to be against secret societies. Thus, while I regard the party of ’43 a libertarian party, I regard the party of ’48 as, at best, a liberal party, and at worst, yet another conservative party. In any event, the party nominated Gerrit Smith of New York that year for the presidency, and for the vice presidency, Charles C. Foote of Michigan.

Address of the Liberty Party to the Colored People of the Northern States

1848 — This address was issued by the Liberty Party in its 1848 convention, stressing to blacks that they should strive to be better men and women than whites, in order to demolish the stereotypes that harm the black community. The address also questions how any black voter could vote for the despicable Henry Clay, a man who “exceeds any other man in responsibility for the sufferings of the negro race.” The address encourages blacks to reject, en mass, pro-slavery churches and pro-slavery parties, and regards both the Democratic and Whig Parties as de facto pro-slavery parties.

The Liberty Party of the United States, to the People of the United States

1848 — This address was also issued by the Liberty Party in its 1848 convention, and it focuses primarily on its constitutional defence of its abolitionist agenda. While the party openly disagrees with Garrison’s condemnation of the Constitution as a pro-slavery instrument, it, interestingly, shows some respect for the Garrisonian position; it takes a far harsher look at those antislavery men who had attempted allegedly to moderate the antislavery position of the Liberty Party in 1847, and who run what Smith regarded as moderately antislavery newspapers, such as the National Era. To the Garrisonians, they say, as long as you continue to believe that the Constitution does condone and create slavery, do continue to reject the document as a compact with Hell.

While Gerrit Smith had, in 1844, argued that slavery was unconstitutional, in much the same way this address to the people argues, what makes this address interesting is that it puts forward the same argument Spooner did in 1845: “One of its excuses for arraying itself on the side of the slaveholder, is, that they intended it should, who framed the Federal Constitution. No such intentions, however, are expressed in that anti-slavery instrument: and it is the expressions of an instrument—not the intentions of its framers—which should govern the interpretation of it. The intentions of the framers of the Constitution are entitled to no more weight in the ascertainment of its meaning, than are the intentions of the scrivener in determining the sense of the Deed, or Contract, which he had been employed to write.” Thus, the party adopted, in part, Spooner’s position that constitutional analysis ought to employ original meaning-styled textualism and rejects original intent-styled originalism.

The proclamation is also interesting, in that it expounds some views that are often principled, and others, that are often horribly confused.

On the one hand, the party sees fit to adopt the two great libertarian positions: viz., (1) opposition to slavery, and support for its immediate abolition; and (2) an opposition to war, as well as to the maintenance of standing armies, which the party claims is more likely to perpetuate, than to prevent, war. Other issues of the left, adopted by this party, include: a support for universal suffrage, irrespective of gender or race; opposition to tariffs, and all other protectionist policies; opposition to all various indirect taxes; distaste for large governmental debts; opposition to government monopoly on land, and of the monopoly of the United States Post Office on the delivery of first-class mail; advocacy of a strict separation between school and state; a general rejection of the view that its the government’s, rather than the people’s, job to build roads and canals; rejection of the view that government should actively organise labour, rather than to merely protect it; and a general advocacy of free trade.

But, the party also unfortunately adopts a variety of right-wing policies, including: promotion of a graduated income tax; condemnation of private trade in land; failure to support the complete abolition of the United States Post Office; support for violent invasion by the state against the consumers, producers, and sellers of alcohol (as well as, one might presume, other mind-altering drugs) on the flimsiest of excuses; support for violent invasion by the state against the property of gamblers; support for violent invasion by the state against the bodies of prostitutes; the concession that governments may build roads or canals in certain circumstances, as well as provide for the erection of light-houses and other such things; and promotion of the view that the government should violently suppress any labourer who wishes to work for more than ten hours a week, and of any employer who would be willing to acquiesce in the wish of such a labourer.

Perhaps, instead of saying that the party of ’48 was, at best, a liberal party, and at worst, yet another conservative party, it might be realistic to say that it took the position of a middle-of-the-road party, one aiming to achieve many liberal ends (e.g., prosperity, equality, peace), but through the conservative means of statism. Of course, as Murray N. Rothbard’s 1965 essay “Left and Right: The Prospects for Liberty” points out, such a programme is ultimately doomed to fail to achieve its liberal ends.

1849 — The next Liberty Party National Convention was held on 3 July 1849, in Cazenovia, N. Y. Again, the party opts to advocate a variety of good positions along, unfortunately, with a variety of tyrannical ones. One very interesting fact, however, is that in clause 22, the party officially endorses a book by the radical libertarian Lysander Spooner. While the platform does not give the title of the book being endorsed, it is unlikely to be any other than The Unconstitutionality of Slavery (1845).

1852 — The Liberty Party held another National Convention on 30 September 1852, in Syracuse, N. Y. It nominated for president, William Goodell of New York, and for vice president, S. M. Bell of Virginia. Interestingly, the party opted to drastically cut back it platform in 1852, allowing only four planks to remain. Here, the party retains its libertarian support for abolition of slavery and its right-wing support for alcohol prohibition.

In 1852, Gerrit Smith was elected to the United States House of Representatives as a Free-Soiler. Nevertheless, he still saw himself as a member of the Liberty Party.

The Civil War

Both Gerrit Smith and Lysander Spooner would later claim that that South had not committed treason in its attempt to secede from the union. Nevertheless, both men remained stridently abolitionist until the days they died.

William Lloyd Garrison (1805–1879)

Myron Holley (1779–1841)

James G. Birney (1792–1857)

Salmon P. Chase (1808–1873)

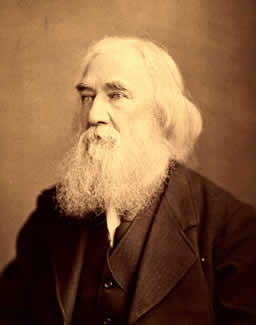

Lysander Spooner (1808–1887)

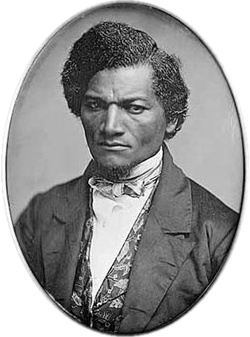

Frederick Douglass (circa 1818–1895)

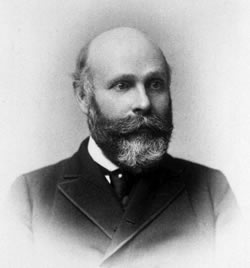

Gerrit Smith (1797–1874)

William Goodell (1792–1878)