Revolution

1215 — Originally written in Latin, Magna Carta is usually translated in English as Great Charter. With this document, the English subjects forced King John of England to acknowledge certain rights held by the people, including what would become the writ of habeas corpus. Although not a perfect document by any stretch of the imagination, this text is to be valued for the progressive and revolutionary limitation of power it entailed.

Discourse of Voluntary Servitude by Étienne de La Boétie

Circa 1553 — La Boétie questions why it is that tyrants are able to oppress the masses when the masses are so many and the tyrants are so few.

Of the Dissolution of Government by John Locke

1690 — Chapter XIX of Locke’s Second Treatise on Government, this text presents Locke’s view on why it is not unjust to overthrow one’s ruler. This text can be easily contrasted with Thomas Hobbes’s Leviathan in which Hobbes claims that one may never dissolve her bonds with her sovereign.

Give Me Liberty or Give Me Death by Patrick Henry

23 March 1775 — This speech, given by Patrick Henry at the second Virginia Convention, argues in favour of defence against the British armies, detailing the alternative as submission and slavery. Patrick Henry unfortunately becomes, later in life, rather conservative when, some years later, rebellion breaks out in Massachusetts, but this speech nevertheless stands the test of time as a truly radical pronouncement.

Common Sense (3rd. ed.) by Thomas Paine

14 February 1776 — This pamphlet, first published anonymously on 10 January 1776, promoted the revolutionary concept of American secession from the British crown. The pamphlet, described by historian Gordon S. Wood as “the most incendiary and popular pamphlet of the entire revolutionary era,” was very popular among Americans, 500,000 copies having sold in the first year alone.

The Declaration of Independence

4 July 1776 — Drafted by Thomas Jefferson, edited by the Committee of Five, and approved by the Second Continental Congress, this was the document of the American revolution, detailing our greviances with King George III and declaring our independence from the British Empire. Some authors consider the war “the revolution”; I, however, consider this document “the revolution.”

Civil Disobedience by Henry David Thoreau

1849 — Although not explicitely an argument in favour of revolution per se, this essay—written to describe how one can fight such evils as slavery and taxation—has very revolutionary implications, and has served as inspiration for various acts of civil disobedience since.

The Spirit of Revolt by Peter Kropotkin

1880 — Kropotkin describes the sentiments that swell amongst the masses prior to culmination of outright rebellion against the status quo, including changing moral outlooks.

Anarchism and American Traditions by Voltairine de Cleyre

December 1908 and January 1909 — In this essay, published in Mother Earth 3, no. 10–11, Cleyre explores the simularities between the revolutionary republicans of ’76 with the anarchists of her day, endeavouring to show that even the limited state power established by the republicans was easily perverted for the benefit of the state. She quotes often that great yet flawed revolutionary Thomas Jefferson.

The Moon is a Harsh Mistress by Robert A. Heinlein

1966 — This classic science fiction novel involves revolutionaries living in 2075 on the moon who rebel against the Terran world government.

The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution by Bernard Bailyn

1967 — Bernard Bailyn, in reading pamphlets and other tracts written in the years leading up to the American revolution, noticed various trends and simularities in the thinking of the various writers. From these texts, Bailyn was able establish what the revolutionary ideology had largely been

From Government to Laissez Faire by Linda & Morris Tannehill

March 1970 — Chapter 15 of The Market for Liberty, this describes a radical method of ending statist oppression, viz. homesteading the “property” of the state.

Conceived in Liberty (4 vol.) by Murray N. Rothbard

1975–1978 — Conceived in Liberty is Rothbard’s history of the American colonies. After briefly describing trade and politics in pre-American Europe, Rothbard begins his tale with the European settlers and takes us all the way to the American Revolution. The author touches on everything, from war waged upon the natives to the struggles for religious tolerance, from slave revolts to tax rebellions. This is the book to read on the American Revolution.

New Libertarian Manifesto (4th. ed.) by Samuel Edward Konkin III

October 1980 — This is the 2006 KoPubCo edition of Konkin’s agorist manifesto for libertarian revolution, which argues that party activism will never yield a stateless society, and that to fight the oppression and tyranny of the state, one must engage in counter-economic activity, that is eschewing the white and red markets in favour of the grey and black.

Toward a Theory of Strategy for Liberty by Murray N. Rothbard

February 1982 — In chapter 30 of The Ethics of Librety, Dr. Rothbard applies the thinking of Marxist revolutionaries to the needs of the radical libertarian movement.

V for Vendetta by Alan Moore

March 1982–May 1989 — This fictional account of an anarchist superhero constitutes my favourite graphic novel. Released as ten separate issues in the ’80s, it takes place in England in the late ’90s after England has descended into fascism. Our hero, known only as V, engages in a successful revolution against the state. In 2006, the novel was adopted into a film of a similar title.

Shays’s Rebellion: The American Revolution’s Final Battle by Leonard L. Richards

2002 — Shays’s Rebellion took place in 1787 in Massachusetts. Although the people had a number of greviances with their state, this rebellion was primarily a tax rebellion. Although the real reason the state had such difficulty putting the rebellion down was not a lack of federal support—instead, it was because everyone in the state supported the rebellion—nationalists twisted the facts to ensure a new Constitution would be drafted granting far too much power to the central state. Richards explains the fascinating story in wonderful detail.

Natural Elites, Intellectuals, and the State by Hans-Hermann Hoppe

???? — I include this essay despite some strong objections to Hoppe’s more conservative orientation. While both Hoppe and I reject both monarchy and democracy, Hoppe sees monarchy as the lesser of the two evils and I see democracy filling the role of the lesser evil. I also find Hoppe’s seeming disdain for the “common man” and his “proletarian mass-culture” unsettling; I have elsewhere in fact claimed, contra Hoppe, that libertarianism as the ideology of and for the common woman and man. I nevertheless include this because of the importance it demonstrates in understanding and undermining the state’s intelligentsia of apologism. It is thus of notable value to radicals wishing to do away with statism.

Untold Truths About the American Revolution by Howard Zinn

6 July 2009 — Zinn argues that the war for independence needed not be a war. Other than Zinn’s claim about Canadian healthcare, this is a generally interesting critique. Zinn’s only main flaw here is that he implies that the revolutionary leaders all wanted independence for the same reason, viz power. In this, he fails to distinguish the federalist from the liberal. The federalist holds a pessimistic view of human nature, believing man to be in need of strong leaders and believing himself to be just the sort of leader, with just the right vision, people need. The liberal revolutionaries, on the contrary, had as their overarching goal the liberation of woman and man. Now would be a good time for me to reiterate my view that the war was not the revolution. Thus, we need not say the revolution was bad in order to say that unethical and depraved acts were carried out during the war.

A Note: There are yet many works on revolution that I have yet to read. For example, I want to read Lenin’s The State and Revolution, for, although I wholly reject the doctrine of state communism, I am nevertheless sure there will be something of value in that text. Another work I wish to get around to reading is On Revolution by Hannah Arendt. And I own, but have not yet read, On Guerrilla Warfare (1937) by the murderous statist Mao Tse-tung.

I have also not read, but would nevertheless never recommend, The Anarchist Cookbook (1971) by William Powell. According to CrimethInc., the book was “not composed or released by anarchists, not derived from anarchist practice, not intended to promote freedom and autonomy or challenge repressive power—and was barely a cookbook, as the recipes in it are notoriously unreliable.” CrimethInc. has released their own Recipes for Disaster: An Anarchist Cookbook, on which I cannot comment further as have not yet read it also.

King John of England signing Magna Carta on June 15, 1215, at Runnymede; coloured wood engraving, 19th century

Battle of the Boyne (1781) by Benjamin West

The Declaration of Independence (1795) by John Trumbull

The Death of General Mercer at the Battle of Princeton (circa 1795) by John Trumbull

Shays’s Rebellion

La Liberté guidant le peuple (1830) by Eugène Delacroix

Black Americans fighting for their rights in the 1960s

Tank Man (1989) by Jeff Widener

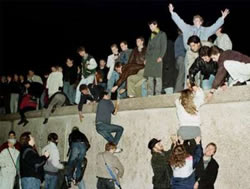

Droves of East Germans defy their government in 1989